Too Specialized–The Other Kiss of Death

I wrote recently about avoiding the Career Kiss of Death by avoiding becoming a commodity. Becoming too specialized can also be a kiss of death. I once worked for an electronic publisher that published legal information. At the time, there were only two companies that did that. I was an expert on the legal data published by my company, the sources of that data, the processes used to publish it, and the customers who bought it. There was only one other company who could use that expertise at that time, and I had a pretty unbreakable non-compete agreement that foreclosed going to work for them. When I looked around, I couldn’t see any option (I wasn’t as creative then as I am now) for a different job/company than the one I had. It’s a really good thing that I really liked the job/company at the time. It’s interesting that now there are lots of companies that could use that expertise. The job market has expanded through the growth of the industry. You can’t count on that happening, though.

I decided at the time that I would expand my marketability by learning expertise about other kinds of data besides legal data. I still had the expertise on how to manage/convert/acquire and sell online information, but I learned how to do all those things with other kinds of data—financial and news. It still seemed too limited to me, though, so I decided to Genericize Myself by learning expertise that crossed industries. (The present online information industry that exists now was unimaginable then!)

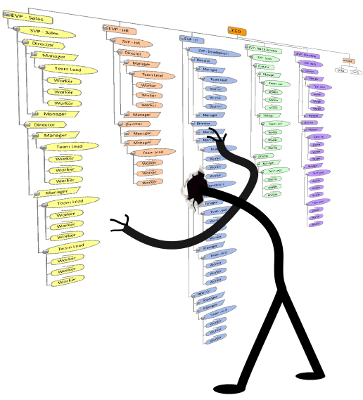

I became an expert on organizational operations. I learned how to improve processes, how to re-engineer processes and how to streamline them. I was successful at improving the processes in my own department, then I began to be sought to help with processes across other departments, and then across organizations owned by my parent company. I didn’t know it then, but I was learning a very marketable skill that has turned into (part) of my career. I have expanded this skill and expertise into a consulting business (that includes other things, but organization process enhancement was the beginning core).

Specialize AND Genericize

Jobs, companies, and industries go away. You need to keep your eye on the horizon of all of these. At the same time, you need to have deep skills—be the company expert, while you are working on making sure that you have genericized to the point that other jobs, companies and industries can use your skills. This may seem like contrary advice, but it isn’t. When you are a deep expert in an area that many companies and industries need, then you are recession-proof. If one company or industry starts to have problems and starts downsizing, then you can move to another. You can continue to land on your feet and continue to grow you skills more deeply to expand your marketability.